Eat garlic, gargle with vinegar and baking soda while standing on one leg! While we are astonished by the growing amount of “medical folklore” for coronavirus treatment, the world eagerly awaits the first unfake news that humanity is on the trail of discovering proper treatment for COVID-19. As a community interested in bringing transparency to the scientific process, the Canadian Open Neuroscience Platform (CONP.ca) organized an online panel focused on open science during the COVID crisis.

The panel was moderated by Nikola Stikov and Rachel Harding, and the guests were Richard Gold, an intellectual property expert in medicine at McGill University, and Dylan Roskams-Edris, Open Science Alliance Officer for The Neuro in Montreal. The occasion for the panel was Richard Gold’s article published in the magazine “Fortune” about the failures of the current model of industrial drug development.

How do you practice open science and what does open science mean to you?

Richard Gold

Full Professor

James McGill Professor

Associate member, McGill Department of Human Genetics

Richard Gold: At a minimum, open science is the belief that sharing is better than not sharing. If I have data, I should share it because you may make better use of it than I can. What’s more, if I share with you, you’’ll also share with me. And it goes beyond data, to tools and materials. In its essence, it is the understanding that science should be open to everyone. This builds trust in science.

The type of open science experiment that the Structural Genomics Consortium and the Montreal Neurological Institute are conducting is to create partnerships with very specific goals. In relation to COVID for example, we want the next best ventilator to be produced at a low price for developing countries, or in terms of the Neuro, we want to develop drugs for neurodegenerative diseases. That Consortium engages in radical sharing both internally and externally, not only of the data and the publications, but everything in between. While the sharing is with everyone, the partners are best positioned to use it.

Open science tries to bring together different kinds of actors motivated by different purposes. So you have firms that are motivated by profit; you’ve got academics, who are motivated by tenure, promotion, or a Nobel Prize; you’ve got patient organizations that are engaged because they want effective treatment … And all these parties work together, they bring their own resources and coordinate different activities.

Dylan Roskams-Edris: I want to put this in the COVID context. I think we are seeing the development of concentrated efforts in fast forward. It started out with people identifying that there was a problem going on, and sharing their data. The original genetic sequence of the virus was shared in early January by a lab in Shanghai, and then a whole bunch of people started sharing their data, code and their preprints.

And then over time, people started realizing that just flooding information isn’t exactly the most useful thing. We need some effort to collect and curate and make sure that everything is high quality. So one example would be a whole bunch of people doing sharing of preprints and open access articles. And then you have a consortium of Microsoft and the Allen Institute for artificial intelligence and CZI coming together and collecting all those manuscripts and then launching a targeted competition in an effort to leverage AI and the existing framework of Kaggle competitions to analyze those preprints.

This is the kind of thing that would have happened over the course of years prior to COVID-19. And yet COVID-19 comes around and all of a sudden, within a couple of months, you see this evolution towards more targeted approaches.

It’s clear that doing open science and practicing it in real-time is the fastest way to get information out quickly. We see it now with the COVID-19 outbreak, but is this going to continue in terms of other disciplines and other research after the pandemic ends?

Richard Gold: What we have seen in science for the last 30 years is a reliance on a small network of people producing knowledge. We have a high-cost system of drug discovery, because everybody’s in their own silos, producing their own data and tools but not sharing it. Scientists are often doing similar types of work at the same time, so there’s a lot of duplication going on and when they engage with one another, they have to negotiate agreements, settling the terms and rights, and that slows down the project. Usually, we don’t get access to the data that underlies the research until later.

Richard Gold: What we have seen in science for the last 30 years is a reliance on a small network of people producing knowledge. We have a high-cost system of drug discovery, because everybody’s in their own silos, producing their own data and tools but not sharing it. Scientists are often doing similar types of work at the same time, so there’s a lot of duplication going on and when they engage with one another, they have to negotiate agreements, settling the terms and rights, and that slows down the project. Usually, we don’t get access to the data that underlies the research until later.

So science moves slowly. Science often needs big equipment, it needs partnerships. If you’re a firm, you’re going to say: “Look, if I do something really new, out of the box thinking, my risk is huge and my chances of success aren’t terribly high. Now, if I succeed, there’s a huge payoff, but my risk upfront is really high. So maybe it’s better that instead of doing something high-risk I investigate something that’s already been done before, I’ll work on a me-too drug”. And that is what’s happening: firms develop me-too drugs, we’re getting less risk-taking and therefore there are fewer breakthrough insights from industry.

And on the academic side, scientists don’t want to take a risk either. You don’t want to investigate something that has a high chance of being useless so you do something safer. We know from bibliometric studies that articles in high impact journals are less novel, on average, than those in lower impact journals. That’s simply the way the system is created – leading us to low innovation.

With open science, we hope to solve that problem. By radical sharing and by simplifying agreements where there’s no intellectual property on the table, we can bring down costs. If the government’s paying for part of it, philanthropies paying for part of it, academics paying for part of it, the cost analysis is different and I’m now more willing to engage in high risk research because each party only bears a part of the cost. We can go after the bigger payoff of breakthrough research when we work together. What we’re trying to do is to change the landscape so that more scientists and more firms will engage in this high risk research. Once that happens, you let people go to patents on downstream innovations and they compete and improve the product.

In the COVID-19 crisis, everybody instinctively recognizes that patents are going to be irrelevant. By the time you get a patent on COVID-19 drug, the pandemic hopefully is gone. So we’re working in a world where people realize that I’m not going to get a drug that’s going to have a big market value and so there, they instinctively move to reduce the costs by working together. And we’ve seen great progress in just a few months in terms of sequencing of the virus, in terms of development of diagnostics, and so on.

Dylan Roskams-Edris: Equally important is expanding into drugs that pharmaceutical companies have generally seen as not worth developing. Vaccines being a prime example. It’s not something that you can give multiple times and then make money over the course of treatment, it’s something that you get once and if it’s a proper product, then it will continue to work. The idea of investing a whole bunch of money into a potentially risky project that will then give you a drug that you can give once is not as enticing. However, if you distribute the cost and use radical sharing to make things as de-risked as possible before reaching the point of having to invest in a clinical trial, then it’s a lot more incentivizing for private companies who have the expertise to take things through clinical trials to actually invest in these types of endeavors. So that means you’re not only going to have higher risk projects being undertaken, but also projects that have been traditionally neglected by your standard pharmaceutical development model.

Dylan Roskams-Edris: Equally important is expanding into drugs that pharmaceutical companies have generally seen as not worth developing. Vaccines being a prime example. It’s not something that you can give multiple times and then make money over the course of treatment, it’s something that you get once and if it’s a proper product, then it will continue to work. The idea of investing a whole bunch of money into a potentially risky project that will then give you a drug that you can give once is not as enticing. However, if you distribute the cost and use radical sharing to make things as de-risked as possible before reaching the point of having to invest in a clinical trial, then it’s a lot more incentivizing for private companies who have the expertise to take things through clinical trials to actually invest in these types of endeavors. So that means you’re not only going to have higher risk projects being undertaken, but also projects that have been traditionally neglected by your standard pharmaceutical development model.

I mean, you know, we’ll solve COVID, but the point is also to help with neurological diseases, to help with neglected tropical diseases, to help with development of antibiotics, to help with vaccines… a whole bunch of things that have seen failure after failure after failure.

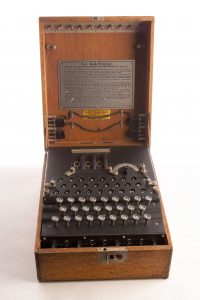

Sometimes these kinds of discoveries happen during times of war, like the Enigma machine or the radar – inventions that are really motivated by a very urgent threat. And this virus is one of those threats that humanity is facing at the moment.

Dylan Roskams-Edris: One of the things that typifies those inventions is that you have an absence of scarcity, right? When Turing was working in Bletchley Park, if he needed something, whether it was a piece of knowledge or a piece of technology, the massive apparatus of British government was getting it for him. If we make sharing, as well as proper documentation and all of that the status quo, then we can create that lack of scarcity without having to rely on a war or a massive bureaucracy. And that would be fantastic.

Dylan Roskams-Edris: One of the things that typifies those inventions is that you have an absence of scarcity, right? When Turing was working in Bletchley Park, if he needed something, whether it was a piece of knowledge or a piece of technology, the massive apparatus of British government was getting it for him. If we make sharing, as well as proper documentation and all of that the status quo, then we can create that lack of scarcity without having to rely on a war or a massive bureaucracy. And that would be fantastic.

In the meantime, we have the Open COVID pledge, a new kind of license agreement about any knowledge discovered around the COVID-19. Signatories of this pledge say that they're not going to file for traditional IP, such as patents. What does this pledge mean and could we get something that could be expanded upon and be applied in other contexts?

Richard Gold: This is a nice gesture, but frankly I don’t think it’s going to result in much. If we are talking about technology that exists today that can be repurposed for COVID-19 – I think the pledge is useful there. But in terms of finding a treatment that’s long lasting, or a vaccine, it doesn’t really do very much, because those things haven’t yet been invented. So they have to be invented, you have to file a patent and the patent doesn’t issue for three years. So, we don’t have to worry about patents.

Richard Gold: This is a nice gesture, but frankly I don’t think it’s going to result in much. If we are talking about technology that exists today that can be repurposed for COVID-19 – I think the pledge is useful there. But in terms of finding a treatment that’s long lasting, or a vaccine, it doesn’t really do very much, because those things haven’t yet been invented. So they have to be invented, you have to file a patent and the patent doesn’t issue for three years. So, we don’t have to worry about patents.

I think as a solution to the COVID-19 crisis, either coming up with vaccines or treatments, it’s the radical sharing right now that is far more important than a pledge not to enforce a patent later on. The governments around the world already have the power by threatening companies and saying: “We’re just going to override your patent with something called a compulsory license”. It’s designed for exactly the situation where the government can come in and say: “I know you have a patent, but if you’re not going to allow other people to use it – we will”. And so the companies also face public pressure. So while a pledge is nice to have, it’s mostly a PR move for the firms involved.

Open science and data sharing raise the issue of privacy. Can you give us some examples of different countries handling privacy issues during the COVID crisis?

Dylan Roskams-Edris: To be able to track people and do contact tracing and to be able to identify when people should be staying inside and self-isolating is important, obviously, if you want to have appropriate medical treatment and prevention. But on the other hand, that kind of information is never restricted to a particular use. So we start getting into interesting governance issues, and you see different approaches across different countries.

In Asia, the Chinese and Korean examples, we see they’re much more willing to make sure that they put up temperature readers all over the place and to do widespread testing, and they say that they’re going to use that data however they see fit. In the Western countries we are a little bit more hesitant to do that.

There are a couple of different models you can use to ensure that privacy is more protected. In South Korea they have collected a whole bunch of data from health records based on people who have tested positive for COVID-19 and they are proposing a model where that data can be analyzed without actually releasing it. Korea says: “You can apply to us, if you have a good proposal, we’ll send you a sample of data, you can see how the data is structured and then write a piece of code that you then submit to us, we’ll run it on the data and share the results back to you.” That’s a better way of protecting privacy than just, for example, trying to anonymize or de-identify the data, and then send it out.

Richard Gold: One of the things that has concerned me for the last several years is how do we come up with structures to ensure privacy. The structure Dylan gave you is basically a two tier structure, where at the bottom level is data that is fully identified, and then we have a second tier where there’s some committee that controls it. At that second level we have data that we can make accessible as in that Korean example. So I think we have to accept that there’ll be some leakage, but I think we still want to protect privacy, that’s an important value here.

Richard Gold: One of the things that has concerned me for the last several years is how do we come up with structures to ensure privacy. The structure Dylan gave you is basically a two tier structure, where at the bottom level is data that is fully identified, and then we have a second tier where there’s some committee that controls it. At that second level we have data that we can make accessible as in that Korean example. So I think we have to accept that there’ll be some leakage, but I think we still want to protect privacy, that’s an important value here.

Unfortunately, some rules we’ve designed prior to open science and a lot of European rules around privacy are overly limiting. We agree with their purpose, but they should be creating exceptions that protect privacy while adjusting to the need for openness. We want access to the data while keeping in mind the fact that our needs for data in five years will be different than they are today. Because of new technologies, new approaches will come out in five years and one extra bit of data could have made a huge difference. If it’s anonymized, we can’t go backwards. What we really need to have is a pool of fully unidentified data that we can somehow revise as time goes on and needs change.

We also have to make sure that patients are allowed to consent to broad use, possibly even general use of their data. If we can’t allow a patient to consent to all conceivable uses, to me that is taking away their autonomy. What we’re seeing at the Montreal Neurological Institute is an enthusiasm to participate in research where that same sample and that same data will be used multiple times. I think we’re doing a disservice to patients by being too paternalistic in saying you can only consent thus far. I think most patients actually want to give broader consent while still enjoying some protection of their privacy.

QUESTIONS FROM THE ATTENDEES

Are there any examples of successful COVID-19 collaborations or advances that have happened as a result of open sharing and open scientific practices?

Dylan Roskams-Edris: There are two examples I want to bring up. One, the incredibly short period between the sharing of the virus sequence and the beginning of a trial, i.e. the original identification of a problem and the development of an application. There’s a trial in the United States, which started 63 days after the original sequence was shared. In the interviews with the company, it’s specifically said that the originally shared sequence was the main reason they were able to move so quickly. Also, I read that the Gates Foundation is scaling up seven different manufacturing facilities and capabilities for seven potential treatments. Not all seven are going to work, maybe one, two, maybe three will be effective… So that’s another kind of thing where a group committed to open science has been laying the ground to roll things out really, really quickly.

Another example is a company called Opentrons that makes equipment for automating research. They are an open hardware company and because they don’t have IP concerns they can rapidly move their equipment out and enable people to modify it and they’ve been pushing towards creating automated testing for COVID-19. So the idea is that with six of their machines in one facility, you can scale up to 10,000 tests a day.

The bright side of the whole situation is that people are starting to realize the importance of science and scientists. But the problem is that very few of the practicing scientists are involved in political activities, trying to change the system from within. What's your opinion about scientists taking this opportunity to get involved in policy?

Dylan Roskams-Edris: What’s important right now in the midst of the crisis for those of us not going into the lab and doing research on COVID-19 is to identify and document the importance of sharing and the importance of the involvement of scientists in making political decisions. So identify, name, and then afterwards advocate with example why it’s important to involve scientists in the political decision making process and why it’s important to change the incentives when it comes to research.

Richard Gold: We already have networks of scientists who work together. Scientists have undertaken the Human Genome Project. When SARS-1 came out, there was significant sharing. So we already have the building blocks for open science. But what we haven’t achieved yet is to convince people to actually believe their eyes, believe the evidence. People are now seeing that, in fact, open science does work, that there is acceleration in knowledge production.

Richard Gold: We already have networks of scientists who work together. Scientists have undertaken the Human Genome Project. When SARS-1 came out, there was significant sharing. So we already have the building blocks for open science. But what we haven’t achieved yet is to convince people to actually believe their eyes, believe the evidence. People are now seeing that, in fact, open science does work, that there is acceleration in knowledge production.

And policymakers… You know, how many times have I gone to bureaucrats or those working for ministers and talked about open science? And they say: yeah, yeah, yeah… But no one does anything about it. And now, suddenly, they are embracing open science! The conversation has started: COVID-19 is responsible for this. I agree with Dylan that we need to document this and remind them of it, going back to universities and telling them: “You know, what you used to do hasn’t worked, try open science.” There’s some theoretical work on the economics and on the legal side that needs to be done, but I think we need to take advantage of the crisis to change the way we do things..

The idea is that we’re learning a ton. People are starting to pay attention to open science. The question is: can we capitalize on this? There’s a tipping point that needs to be reached, where people simply accept open science as a way of doing research and development. We need patient groups to push it, we need more institutions behind it. The field of rare diseases is a perfect example where the existing system does not provide incentives. If we can just get granting councils and foundations to start issuing open science calls…if we get 15% of science working in the open and that becomes successful, then this approach will take over.

You know, it’s really your generation that’s going to drive the change. Older generations were doing other things, but this must be driven by the young researchers and stories like Rachel’s. There is this fear that if I share everything, I’m never going to get hired, nobody would want to work with me, and the fear is unjustified. The idea of open science will succeed if you can attract a new generation of researchers who believe in open science even if the administration fails to acknowledge it properly. So the question is: Will it happen next year? Or when enough of us are convinced that it’s the right thing to do? Are we looking at a 10 year horizon? I don’t know. But I’m convinced that it will happen!